Read time: 8 minutes.

Narjust Florez, MD, is the associate director of the Cancer Care Equity Program and a thoracic medical oncologist at the Dana-Farber Brigham Cancer Center. She founded the Florez Lab in 2019, which focuses on lung cancer, social justice issues in medicine, and medical education. The laboratory’s long-term goals are to create a welcoming environment for medical trainees from historically underrepresented groups in medicine while improving the care of vulnerable populations

Lung cancer remains one of the deadliest cancers worldwide.1 Among women, it is the second most diagnosed cancer2 and in the United States is the number one cause of cancer-related death,2,3 making it an increasing issue in women’s health. Despite being traditionally associated with older men and tobacco use, lung cancer rates are rising among women—particularly younger women.4

In 2021, lung cancer diagnoses were higher in women under 65 years old than in men, and by 2025, women under 50 are more likely than men to receive a lung cancer diagnosis.5 Women, particularly those who are younger and do not use tobacco, are more likely to be diagnosed with adenocarcinoma-type non-small cell lung cancer and to harbor EGFR and KRAS mutations.6,7,8

General environmental exposures, such as secondhand smoke and occupational hazards, also contribute to lung cancer risk.9,10 However, women face additional gender-specific exposures, particularly from indoor air pollution caused by wood-burning stoves or biomass fuels used for cooking and heating, due to gendered roles related to cooking. Despite having marginally higher survival rates than men, lung cancer in women remains under recognized, and research lags behind the unique needs of these patients. It is crucial for the medical community to understand the distinct challenges of lung cancer in women to raise awareness and address health disparities.

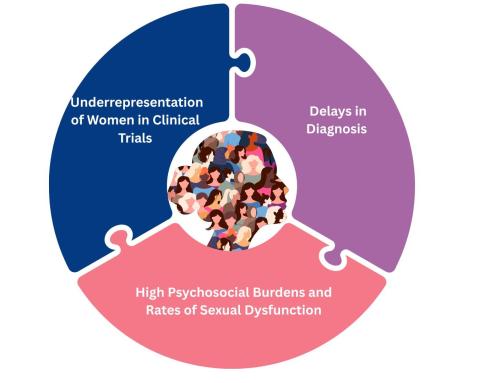

Issue 1: Delays in Diagnosis and Barriers to Screening

Given the rising incidence of lung cancer in women, it is essential to address the barriers that prevent eligible women from being screened and diagnosed early. Diagnostic delays can occur throughout one’s lung cancer care11; however, women face particular obstacles that can hinder a timely lung cancer diagnosis. This includes lower rates of help-seeking for early symptoms, reduced referral to definitive care, and stigma surrounding the disease.12

A retrospective study examining factors contributing to care delays for suspicious lung nodules found that female patients were more likely to experience prolonged referral and biopsy times.13 The longest delays were observed between the initial consultation and biopsy, and from diagnosis to the start of treatment.13 These prolonged waiting periods are concerning, as they can defer the start of treatment, enable progression of disease, and limit potential care options.

Screening limitations and eligibility also remain persistent barriers to diagnosis. While some barriers affect all individuals, such as limited access to care and screening, socioeconomic constraints, stigma, and physician mistrust,14 many disproportionately impact women due to gender bias within the healthcare system.

For example, a study by Warner et al. examining race and sex differences in conversations relating to lung cancer screening found that women were less likely than men to have these discussions with their primary care provider or be aware of screening options.15 As a result, women may miss critical opportunities for early detection. Furthermore, screening-eligible women of color are six times less likely than their male counterparts to be offered screening options, thereby limiting their access to early detection.16

Beyond provider bias, many women are structurally excluded from screening due to stringent eligibility criteria, especially relating to age and tobacco use history. A retrospective cohort study of patients with lung cancer from 2005-2015 found that 80.6% of women with a confirmed diagnosis did not meet the eligibility criteria, with 27.4% excluded due to age and 75.1% due to insufficient tobacco use—less than 30 pack-years.

In 2021, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines for screening expanded their eligibility criteria to include individuals 50 and older and reduced their tobacco use history requirement to 20 pack-years.17 Even with the expanded age range and lower tobacco use requirement for the 2021 guidelines, a retrospective analysis addressing sex disparities in lung cancer screening eligibility found that women are still more likely than men to fall below the USPSTF’s 20 pack-year smoking threshold and therefore be deemed ineligible for lung cancer screening.18

These findings underscore how current screening frameworks, even after revision, continue to overlook a substantial portion of at-risk women, particularly those with minimal or no tobacco exposure. This is especially concerning given there are increased rates of women being diagnosed with lung cancer at younger ages.19 further highlighting how disproportionate screening eligibility negatively impacts lung cancer care for women.

Issue 2: Overlooked Psychosocial and Sexual Health Burdens

Psychosocial and sexual health issues in women with lung cancer are under researched, despite evidence that these women face high rates of depression, anxiety, and diminished functional well-being. A 2022 analysis of over 700,000 individuals revealed that women with lung cancer had significantly higher rates of psychological disorders and reported more feelings of depression and anxiety compared to men.20 This mental health burden may be exacerbated by stigma or self-blame, as many women report receiving accusatory remarks surrounding tobacco use status upon diagnosis, regardless of their tobacco use history.21,22

Preliminary data from our own Young Lung Cancer Psychosocial Needs Assessment, which was composed of 69% women, revealed that more than one-third of participants reported a new mental health diagnosis since their lung cancer diagnosis.23 Emotional and functional well-being were among the most affected, with patients reporting sadness, anxiety, fatigue, and fear of premature death.23

Sexuality and sexual health are often overlooked in lung cancer care for women, despite their significant roles in identity, emotional well-being, and relationships.24 Although sexual health studies in oncology often focus narrowly on breast and gynecological cancers, evidence suggests that sexual concerns are common for women across many cancer types such as colorectal, head, and neck cancers.25,26

Sexual dysfunction remains a major issue for women diagnosed with lung cancer. Our own Sexual Health Assessment in Women with Lung Cancer (SHAWL) Study, the largest study of its kind, evaluated the sexual health of 249 female participants with lung cancer. Of these, 77% reported moderate to severe sexual dysfunction, with many citing vaginal dryness, discomfort, and pain during intercourse.27 Experiences unique to women with lung cancer, and related to their sexual dysfunction, included fatigue, shortness of breath, and body image changes.28 The responses from this study highlight the urgent need for increased awareness and conversations about sexual health, as addressing these issues can improve overall well-being, pain management, and relationships.28

Issue 3: Lack of Women’s Representation in Clinical Trials

A long-standing issue in women’s health is the lack of representation in clinical trials. As of 2019, women made up only 40% of clinical trial participants focused on diseases that disproportionately affected them, such as cancer, psychological disorders, and cardiovascular disease.29 Further research on non-small cell lung cancer-specific trial enrollment between 2003-2016 and 2010-2020 showed that women represented 38.7% and 39% of participants, respectively, indicating little progress over time.30,31

Barriers to trial participation have included travel distances and expenses, distrust of the medical community, and limited awareness of available trials.22,32 On top of these challenges, women face additional gender-specific barriers. As primary caregivers, women face additional time constraints that can affect their willingness to participate in research.22 Further, gendered assumptions such as women being difficult to work with or less interested in participating influence whether they are offered the opportunity to participate, further diminishing their enrollment into clinical trials.33

These limitations hinder our ability to understand and generalize the impact of treatments on both men and women as we fail to capture sex-specific differences in efficacy, side effects, and outcomes of cancer treatments. A meta-analysis of over 3,500 patients undergoing immunotherapy, targeted therapy, or chemotherapy in a cancer trial from 1980 to 2019 showed that women were 25% more likely to experience more severe adverse events.34 However, another study examining the prevalence of adverse event reporting among patients receiving oral targeted cancer treatments found that women were less likely to report those events.35 Further, our own analysis of 476 women with metastatic melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer found that pre-menopausal women were at the highest risk for immune-related toxicities.36 These findings highlight the need to increase female representation in clinical trials to improve care and outcomes for all, ensure equity, and develop safer, more effective medicines based on sex-specific responses.

Solutions and Next Steps

Women’s health is complex, influenced by a combination of biological, social, and systemic factors that warrant deeper exploration. While the challenges they face are multifaceted, we must start by amplifying awareness and investing in research that centers women's experiences.

This is why my team and I created the #HearHer campaign aimed at increasing awareness surrounding the rising rates of lung cancer in women and their unique experience. Taking shape through an informational card and lung pin, this social media campaign has striven to introduce a global conversation of lung cancer in women while encouraging women within the lung cancer community to share their experiences. Campaigns like #HearHer are crucial for shifting both public and professional perceptions, ensuring that women’s voices, symptoms, and stories are not dismissed, but heard.

Raising awareness is only the beginning. At the Florez Lab, we are turning awareness into action through research that addresses the needs of women with lung cancer. We are taking vital steps toward understanding how lung cancer affects women’s lives at different points of care. This is happening through efforts with studies like FhINCH, which investigates the effects of lung cancer treatments such as TKIs and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) on fertility and reproductive health, and our Pregnancy and Lung Cancer Registry, aimed at learning about both maternal and fetal outcomes in the context of lung cancer treatment.

However, our work is not limited to a research setting. Together, we can lay the foundation for meaningful change and improving both outcomes and quality of life for women with lung cancer.

1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394-424.

2. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts for Women. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/risk-prevention/understanding-cancer-risk/cancer-facts/cancer-facts-for-women.html.

3. McDowell S. Lung Cancer Kills More People Worldwide Than Other Cancer Types. American Cancer Society; 2024. https://www.cancer.org/research/acs-research-news/lung-cancer-kills-more-people-worldwide-than-other-cancers.html.

4. Jemal A, Miller KD, Ma J, et al. Higher Lung Cancer Incidence in Young Women Than Young Men in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(21):1999-2009.

5. McDowell S. Cancer Incidence Rate for Women Under 50 Rises Above Men's. American Cancer Society; 2025. https://www.cancer.org/research/acs-research-news/cancer-incidence-rate-for-women-under-50-rises-above-mens.html.

6. Ragavan MV, Patel MI. Understanding sex disparities in lung cancer incidence: are women more at risk? Lung Cancer Manag. 2020;9(3):Lmt34.

7. Zhang Y, Sun Y, Pan Y, et al. Frequency of driver mutations in lung adenocarcinoma from female never-smokers varies with histologic subtypes and age at diagnosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(7):1947-1953.

8. Chevallier M, Borgeaud M, Addeo A, et al. Oncogenic driver mutations in non-small cell lung cancer: Past, present and future. World J Clin Oncol. 2021;12(4):217-237.

9. Leiter A, Veluswamy RR, Wisnivesky JP. The global burden of lung cancer: current status and future trends. Nature Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20(9):624-39.

10. Cheng ES, Weber M, Steinberg J, et al. Lung cancer risk in never-smokers: An overview of environmental and genetic factors. Chin J Cancer Res. 2021;33(5):548-562.

11. Ellis PM, Vandermeer R. Delays in the diagnosis of lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2011;3(3):183-188.

12. Baiu I, Titan AL, Martin LW, et al. The role of gender in non-small cell lung cancer: a narrative review. J Thorac Dis. 2021;13(6):3816-3826.

13. Rama N, Nordgren R, Husain AN, et al. Factors associated with delays in care of suspicious lung nodules at an academic medical center. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(16 suppl):e13705-e.

14. Haddad DN, Sandler KL, Henderson LM, et al. Disparities in Lung Cancer Screening: A Review. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(4):399-405.

15. Warner ET, Lathan CS. Race and sex differences in patient provider communication and awareness of lung cancer screening in the health information National Trends Survey, 2013–2017. Prev Med. 2019;124:84-90.

16. Florez N, Brown C. Dr. Narjust Florez on the Reality of Lung Cancer in Women. Lung Cancers Today. 2022. https://www.lungcancerstoday.com/post/dr-narjust-florez-on-the-reality-of-lung-cancer-in-women.

17. USPSTF Issues Final Recommendation Statement on Screening for Lung Cancer. ASCO Post. 2021. https://ascopost.com/issues/march-25-2021/uspstf-issues-final-recommendation-statement-on-screening-for-lung-cancer/?bc_md5=INSERT_CUSTOM01.

18. Pasquinelli MM, Tammemägi MC, Kovitz KL, et al. Addressing Sex Disparities in Lung Cancer Screening Eligibility: USPSTF vs PLCOm2012 Criteria. Chest. 2022;161(1):248-256.

19. Howard J. In the US, young and middle-aged women are being diagnosed with lung cancer at higher rates than men. CNN Health. 2024. https://www.cnn.com/2024/11/25/health/lung-cancer-young-women-susan-wojcicki-wellness/index.html.

20. Stabellini N, Bruno DS, Dmukauskas M, et al. Sex Differences in Lung Cancer Treatment and Outcomes at a Large Hybrid Academic-Community Practice. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2022;3(4):100307.

21. Wang Y, Feng W. Cancer-related psychosocial challenges. Gen Psychiatry. 2022;35(5):e100871.

22. Florez N, Kiel L, Riano I, et al. Lung Cancer in Women: The Past, Present, and Future. Clin Lung Cancer. 2024;25(1):1-8.

23. Florez N, Kiel L, Horiguchi M, et al. Young lung cancer: Psychosocial needs assessment. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(16 suppl):12104.

24. Reese JB, Shelby RA, Abernethy AP. Sexual concerns in lung cancer patients: an examination of predictors and moderating effects of age and gender. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(1):161-165.

25. Reese JB, Bober SL, Daly MB. Talking about women's sexual health after cancer: Why is it so hard to move the needle? Cancer. 2017;123(24):4757-4763.

26. Shell JA, Carolan M, Zhang Y, Meneses KD. The longitudinal effects of cancer treatment on sexuality in individuals with lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35(1):73-79.

27. Dana Farber Cancer Institute. Sexual dysfunction high among women with lung cancer. 2022. https://www.dana-farber.org/newsroom/news-releases/2022/sexual-dysfunction-high-among-women-with-lung-cancer.

28. Dana Farber Cancer Institute. Sexuality and Lung Cancer: Addressing the Elephant in the Room. YouTube 2022.

29. Balch B. Why we know so little about women’s health. Assoc Am Med Coll News. 2024. https://www.aamc.org/news/why-we-know-so-little-about-women-s-health#:~:text=As%20recently%20as%202019%2C%20women,more%20commonly%20excluded%20from%20trials.

30. Krishnan V, Fass L, Chaudhry T, et al. Representation of Women in Lung Cancer Randomized Trials– A Systematic Review. Presented at American Association for Thoracic Surgery annual meeting, May 2023.

31. Duma N, Vera Aguilera J, Paludo J, et al. Representation of Minorities and Women in Oncology Clinical Trials: Review of the Past 14 Years. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14(1):e1-e10.

32. Lond B, Dodd C, Davey Z, et al. A systematic review of the barriers and facilitators impacting patient enrolment in clinical trials for lung cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2024;70:102564.

33. Kane A, Mitchell S. Invisible Women: Exploring the need for greater enrollment of women in clinical trials: JMSMA. 2024;65(5/6). https://jmsma.scholasticahq.com/article/117931.

34. Unger JM, Vaidya R, Albain KS, et al. Sex Differences in Risk of Severe Adverse Events in Patients Receiving Immunotherapy, Targeted Therapy, or Chemotherapy in Cancer Clinical Trials. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(13):1474-1486.

35. Monestime S, Page R, Jordan WM, Aryal S. Prevalence and predictors of patients reporting adverse drug reactions to health care providers during oral targeted cancer treatment. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2021;61(1):53-9.

36. Duma N, Abdel-Ghani A, Yadav S, et al. Sex Differences in Tolerability to Anti-Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 Therapy in Patients with Metastatic Melanoma and Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Are We All Equal? Oncologist. 2019;24(11):e1148-e1155.